Sacred Space and Educational Community in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Ages

At today’s universities sacred spaces find only marginal recognition in their architectural settings. However, this project assumes that churches and chapels were the physical centre of the institutional life of educational communities such as universities, colleges or high schools during pre-modern times. Due to the quasi-monastic character of educational communities its members congregated specifically through liturgy. Therefore, since 1300, churches and chapels – and not libraries or teaching rooms - formed the architectural core of a complex spatial structure. This did not change during the Reformation. Rather, it shall be demonstrated that in the following centuries of confessional diversity until the Enlightenment the chapel or church remained the space for the formation of academic identity.

Approach to research: Although a rich inventory of monuments illustrates the central role of sacred spaces in the constitution of the European educational system, art historic research has at best dealt with single monuments without putting them in a broader context. This narrowing approach to the concrete structure neglects both its complex incorporation into the topography of the institution and the paraliturgic character of many pre-modern academic rituals. Therefore, an analysis on various levels of spatial qualities of architecture is required:

- Which architectural and artistic modes were used to create a liturgic space that allowed teachers and learners alike to congregate as an educational community?

- What position did the sacred space inhabit in a processually developing room topography of the respective educational institution?

- Based on the paraliturgic character of academic practices, to what degree did a sacralisation of the topography as a whole take place?

- What were the relations between sacred spaces of different educational communities? More specifically, were there parallels due to the same donor or is there competition between them due to different theological positions after the Reformation?

The central aim of this project is to comparatively investigate the relation between sacred space and higher education in the pre-modern ages under consideration of the categories mentioned above. Such rooms developed as parts of larger ensembles in lengthy and transformational processes. Therefore, the time period around 1500 is not regarded as an (art historical) divide of epochs. Rather, the Reformation is viewed as a catalysing factor through which late medieval concepts of space remained useable for confessional demands of the early modern ages.

|

|

|---|

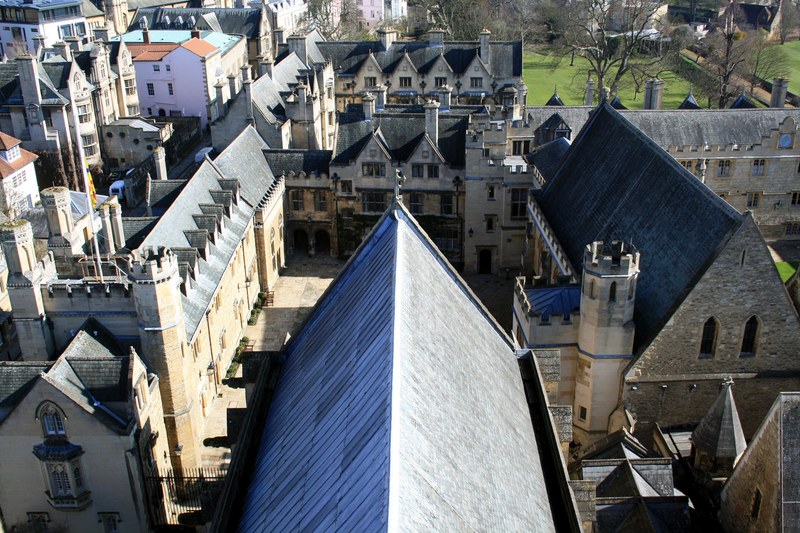

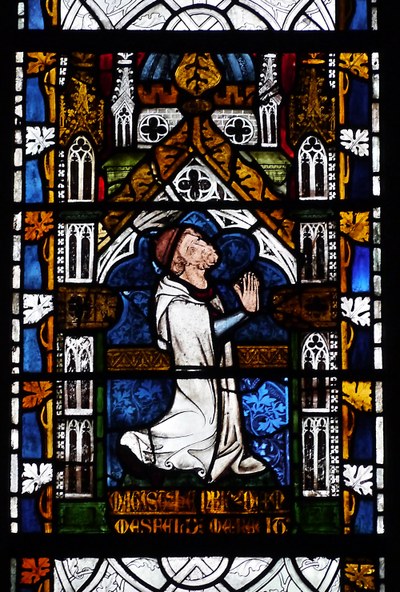

Object of investigation: Such interiors are preserved predominantly in England, i.e. in chapels of colleges in Oxford and Cambridge, as well as their feeder schools such as Eton or Winchester. Moreover, stained glass paintings and murals as well as pews and liturgica are in part still being used to honor the memory of the donor today. Thus, this rich inventory enables the investigation of the systematic role of such sacred spaces as the nucleus of late medieval educational communities as well as of the passing on of medieval concepts of sacred space in newly built chapels and churches up until the 18th century. Based on these research findings sacred rooms in other parts of Europe will be investigated.

Initial research findings were collected during professor Späth’s Visiting Research Fellowship at Merton College Oxford in 2018.

First published results:

Markus Späth: Sakralraum und Bildungsgemeinschaft. Spätmittelalterliche College-Kapellen in Oxford, in: Marburger Jahrbuch für Kunstwissenschaft 45 (2018), pp. 81–106.