Mechanistisches Denken in der Chemie

Mechanistisches Denken ist ein Kernaspekt der Organischen Chemie und gleichzeitig ist das Lösen mechanistischer Problemstellungen sehr komplex und führt bei Studierenden häufig zu Schwierigkeiten. Um tatsächlich vorauszusagen, wie organische Moleküle miteinander reagieren, müssen verschiedenste Eigenschaften von Molekülen und dynamische Veränderungen in den Blick genommen, gedanklich miteinander verknüpft und gegeneinander abgewogen werden. Bisherige Forschungsergebnisse zeigen, dass dies den Studierenden oft nicht gelingt und stattdessen das Auswendiglernen von Mechanismen im Lernprozess eine dominante Rolle einnimmt. Bisher liegen jedoch im Bereich der Organischen Chemie kaum Ergebnisse vor, welche Elemente prozessbezogenen und kausalen Denkens Studierende bereits im Sinne produktiver Ressourcen mitbringen, und wo genau angesetzt werden kann, um ein auf Verständnis ausgerichtetes Lernverhalten zu fördern. Um diese Lücke zu füllen, entwickeln wir ein auf Erkenntnissen der Wissenschaftsphilosophie basierendes Modell mechanistischen Denkens. Die Modellierung von idealtypischen kausalen Verknüpfungen zwischen molekülspezifischen, statischen Eigenschaften und reaktionstypischen, dynamischen Eigenschaftsänderung macht es möglich kontextunabhängige Kategorien als Teilaspekte mechanistischen Denkens zu definieren. Auf dem Modell basierende mechanistische Problemstellungen werden in Interviews mit Chemie-Bachelorstudierenden eingesetzt. Die ebenfalls auf dem Modell basierende qualitative Analyse kann so einen Beitrag liefern, die beschriebene Lücke zu schließen.

Aktuelles Projekt

Meaningful contrasts - Investigating the potential of scaffolded contrasting cases to promote students’ mechanistic reasoning in organic chemistry

(Mitarbeiter: David Kranz)

Reaktionsmechanismen spielen eine große Rolle in der organischen Chemie. Es ist daher nicht verwunderlich, dass es diesbezüglich bereits ein breites Forschungsfeld gibt, dass sich mit dem Ergründen des mechanistischen Problemlösens in dieser Disziplin beschäftigt (u. a. Caspari et al., 2018; Crandell et al., 2020; Deng and Flynn, 2021; Watts et al., 2021).

Ein vielversprechender Ansatz diese Kompetenz zu fördern, stellen Fallvergleiche dar (Alfieri et al., 2013; Graulich and Schween, 2018), die bereits in anderen Studien dieser Arbeitsgruppe zum Tragen kamen (Caspari et al., 2018; Eckhard et al., 2021). Damit Fallvergleiche allerdings optimal eingesetzt werden können, sollte das Bearbeiten dieser angeleitet werden, um Fehlkonzepte und rein oberflächliches Betrachten der Fälle zu vermeiden (Chin and Brown, 2000; Richland et al., 2007; Rittle-Johnson and Star, 2009).

Dafür eignet sich in besonderer Weise sogenanntes Scaffolding (Wood et al., 1976; Belland, 2011; Yuriev et al., 2017). Statt die Fallvergleiche mit einer einfachen Aufgabenstellung wie warum reagiert Reaktion A schneller als Reaktion B? durch Studierende bearbeiten zu lassen, werden die Lernenden mit Teilaufgaben durch den Problemlöseprozess geführt umso Schritt für Schritt vollständig kausale Argumente zu erarbeiten, die von einer Ursache ausgehen und in einem Effekt münden.

In diesem Projekt soll zunächst in einem Mixed-Methods Ansatz überprüft werden, wie Studierende diese gescaffoldeten Fallvergleiche bearbeiten, ob sich dabei wiederkehrende Muster finden und wie das Bearbeiten sowie der Wissenszuwachs vom Vorwissen der Lernenden abhängt. In einer zweiten, quantitativen Studie soll danach die Wirkung von gescaffoldeten Fallvergleichen im Kontrast zu nicht angeleiteten Fallvergleichen und einer Kontrollgruppe untersucht werden, um so den Effekt auf das prozedurale und konzeptuelle Wissen zu erforschen.

Es handelt sich bei diesen Forschungsvorhaben um ein Kooperationsprojekt mit Michael Schween von der Philipps-Universität Marburg.

Alfieri L., Nokes-Malach T. J. and Schunn C. D., (2013), Learning Through Case Comparisons: A Meta-Analytic Review, Educ. Psychol., 48, 87-113.

Belland B. R., (2011), Distributed Cognition as a Lens to Understand the Effects of Scaffolds: The Role of Transfer of Responsibility, Educational Psychology Review, 23, 577-600.

Caspari I., Kranz D. and Graulich N., (2018), Resolving the complexity of organic chemistry students' reasoning through the lens of a mechanistic framework, Chem. Educ. Res. Pract., 19, 1117-1141.

Chin C. and Brown D. E., (2000), Learning in science: A comparison of deep and surface approaches, Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 37, 109-138.

Crandell O. M., Lockhart M. A. and Cooper M. M., (2020), Arrows on the Page Are Not a Good Gauge: Evidence for the Importance of Causal Mechanistic Explanations about Nucleophilic Substitution in Organic Chemistry, J. Chem. Educ., 97, 313-327.

Deng J. M. and Flynn A. B., (2021), Reasoning, granularity, and comparisons in students’ arguments on two organic chemistry items, Chem. Educ. Res. Pract.

Eckhard J., Rodemer M., Langner A., Bernholt S. and Graulich N., (2021), Let's frame it differently – analysis of instructors’ mechanistic explanations, Chem. Educ. Res. Pract.

Graulich N. and Schween M., (2018), Concept-Oriented Task Design: Making Purposeful Case Comparisons in Organic Chemistry, J. Chem. Educ., 95, 376-383.

Richland L., Zur O. and Holyoak K., (2007), MATHEMATICS: Cognitive Supports for Analogies in the Mathematics Classroom, Science (New York, N.Y.), 316, 1128-1129.

Rittle-Johnson B. and Star J. R., (2009), Compared with what? The effects of different comparisons on conceptual knowledge and procedural flexibility for equation solving, J. Chem. Educ., 101, 529.

Watts F. M., Zaimi I., Kranz D., Graulich N. and Shultz G. V., (2021), Investigating students’ reasoning over time for case comparisons of acyl transfer reaction mechanisms, Chem. Educ. Res. Pract.

Wood D., Bruner J. S. and Ross G., (1976), The role of tutoring in problem solving, Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 17, 89-100.

Yuriev E., Naidu S., Schembri L. S. and Short J. L., (2017), Scaffolding the development of problem-solving skills in chemistry: guiding novice students out of dead ends and false starts, Chem. Educ. Res. Pract., 18, 486-504.

gefördert durch die

Abgeschlossenes Projekt

Kausales Denken bezüglich dynamischer, multivariater Systeme

(Mitarbeiterin: Ira Caspari)

This mechanistic step is “productive”: organic chemistry students’ backward-oriented reasoning

Caspari, I., Weinrich, M. L., Sevian, H. and Graulich, N. (2017), Chem. Educ. Res. Pract., 19, 42-59, DOI: 10.1039/C7RP00124J

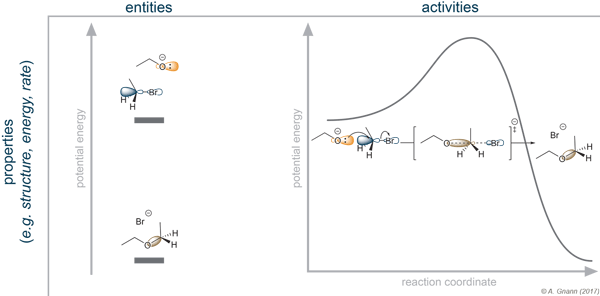

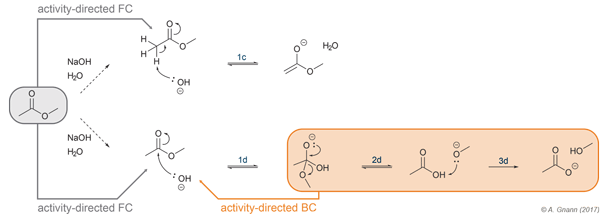

If an organic chemistry student explains that she represents a mechanistic step because “it’s a productive part of the mechanism,” what meaning could the professor teaching the class attribute to this statement, what is actually communicated, and what does it mean for the student? The professor might think that the explanation is based on knowledge of equilibria of alternative steps. The professor might also assume that the student implies information about how one of the alternatives influences the energetics of subsequent steps or how subsequent steps influence the equilibria of the alternatives. Meanwhile, the student might literally mean that the step is represented simply because it leads to the product. Reasoning about energetic influences has much greater explanatory power than teleological reasoning taking the consequence of mechanistic steps as the reason for their prediction. In both cases, however, the same backward-oriented reasoning is applied. Information about subsequent parts in the mechanism is used to make a decision about prior parts. To qualitatively compare the reasoning patterns and the causality employed by students and expected by their professor, we used a mechanistic approach from philosophy of science that mirrors the directionality of a mechanism and its components: activities, entities, and their properties. Our analysis led to the identification of different reasoning patterns involving backward-oriented reasoning. Participants’ use of properties gave additional insight into the students’ reasoning and their professor’s expectations, which supports the necessity for clear expectations in mechanistic reasoning in organic chemistry classrooms. We present a framework that offers a lens to clarify these expectations and discuss implications of the framework for improving student mechanistic reasoning in organic chemistry.

Resolving the complexity of organic chemistry students' reasoning through the lens of a mechanistic framework

Caspari I., Kranz D. and Graulich N., (2018), Chem. Educ. Res. Pract., DOI: 10.1039/c8rp00131f

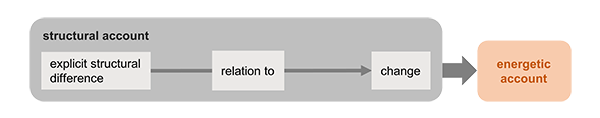

Research in organic chemistry education has revealed that students often rely on rote memorization when learning mechanisms. Not much is known about student productive resources for causal reasoning. To investigate incipient stages of student causal reasoning about single mechanistic steps of organic reactions, we developed a theoretical framework for this type of mechanistic reasoning. Inspired by mechanistic approaches from philosophy of science, primarily philosophy of organic chemistry, the framework divides reasoning about mechanisms into structural and energetic accounts as well as static and dynamic approaches to change. In qualitative interviews, undergraduate organic chemistry students were asked to think aloud about the relative activation energies of contrasting cases, i.e. two different reactants undergoing a leaving group departure step. The analysis of students’ reasoning demonstrated the applicability of the framework and expanded the framework by different levels of complexity of relations that students constructed between differences of the molecules and changes that occur in a leaving group departure. We further analyzed how students’ certainty about the relevance of their reasoning for a claim about activation energy corresponded to their static and dynamic approaches to change and how students’ success corresponded to the complexity of relations that they constructed. Our findings support the necessity for clear communication of and stronger emphasis on the fundamental basis of elementary steps in organic chemistry. Implications for teaching the structure of mechanistic reasoning in organic chemistry and for the design of mechanism tasks are discussed.