SoSe 2019: Contact Zones in the Study of Culture

Leigh York (Cornell University, Ithaca)

Transmedia Contact Zones: Episodes from the Page to the Screen

14.05.2019, 18-20, room 001, MFR

Abstract

This talk will posit the “episode” as the primary narrative unit that shapes multi-media print narratives in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. With the rise of the periodical press, authors were faced with rapidly changing printing technologies and an expanding literary marketplace. Whereas earlier picaresque novels comprised series of episodes that were only loosely connected, new media conditions demanded new narrative strategies. This project looks at the ways that nineteenth-century authors began using the episode to generate complex forms of transmedia continuity that generate continual (and futural) narrative pleasure. By looking beyond its own narrative limits and asking “what comes next,” the episode conveys a storytelling gap that prompts continuation in future episodes, thus generating a potentially infinite series that, in many cases, exceeds the boundaries of text and medium. I trace the development of multi-media episodes from the eighteenth-century work of Karl Philipp Moritz to the nineteenth-century bestseller Karl May; I end by arguing that the episode continues to structure popular transmedia storytelling well into the twenty-first century, in print, online, and on screen. This paper uncovers a continuity between print media in the long nineteenth century and digital media in the twentieth and twenty-first, giving us a deeper historical view of our own storytelling practices and aligning these practices with larger shifts in how we conceive of life, pleasure, value, and politics.

See the recording in our Video Archive

John Haldon (Princeton University)

St Theodore, Euchaïta and Anatolia, c. 500-1000.Landscape, Climate and the Survival of an Empire

11.06.2019, 18-20, room 001, MFR

Abstract

No-one doubts that climate, environment and societal development are linked in causally complex ways. But in relating these different evidential spheres in an explanatorily satisfactory way, we must consider a number of issues, not least the scale at which the climatic and environmental events are observed, and how this relates to the societal changes in question. Differentiating between the various effects of the structural dynamics of a set of inter-connected or overlapping socio-economic or cultural systems is complex; building into our explanation the impact of environmental stressors does not make life easier. One good reason for a historical perspective is to determine how different categories of socio-political system respond to different levels of stress – in the hope that such knowledge can contribute to contemporary policy and future planning, for example. How and why are some societal systems more resilient or flexible than others? If we don’t really understand these complex causal associations, we are unlikely to generate effective responses.

Since Anatolia was for several centuries the heart of the medieval eastern Roman empire, understanding how its climate impacted on the political, social and cultural history of the eastern Roman world would seems to be an important consideration. But only recently have historians begun to think about this seriously and to take into account the integration of high-resolution archaeological, textual and environmental data with longer-term low-resolution palaeo-environmental data, which can afford greater precision in identifying some of the causal relationships underlying societal change. In fact, the Anatolian case challenges a number of assumptions about the impact of climatic factors on socio-political organization and medium-term historical evolution. In particular, the study raises the question of how the environmental conditions of the later seventh and eighth centuries CE impacted upon the ways in which the eastern Roman Empire was able to weather the storm of the initial Arab-Islamic raids and invasions of the period ca. 650-740 and how it was able to expand again in the tenth century. When looked at holistically, the palaeoenvironmental, archaeological and historical data reflect a complex interaction of anthropogenic and natural factors that throw significant light on the history of the empire and its neighbors, offering at the same time a useful approach to similar issues in other cultures and periods.

André Keet (Nelson Mandela University, South Africa)

Racism’s Knowledge/Culture – Is a Critical Decolonial Project Possible?

02.07.2019, 18-20, room 001, MFR

Abstract

Knowledge belongs to racism, and this proprietary relationship exercises steering power over cultural meaning-making processes. This is the straightforward thesis I am exploring here. Though the racism-knowledge nexus and its expression within scholarship and the academy has been a topic of academic interest for many decades, it has been dominated by debates on how racism ‘frames’ knowledge that centers the white, western subject. Another prevailing trend focuses on racism within the disciplines and its disciples, the academy, and the reproductive racialized outcomes of university education. However, my argument, is not simply that racism is inscribed into knowledge systems, but that racism provides the conceptual and pragmatic coordinates for knowledge. This disorder, so I suggest, needs to be tackled head-on to unburden the considerable possibilities for a critical, decolonial knowledge project.

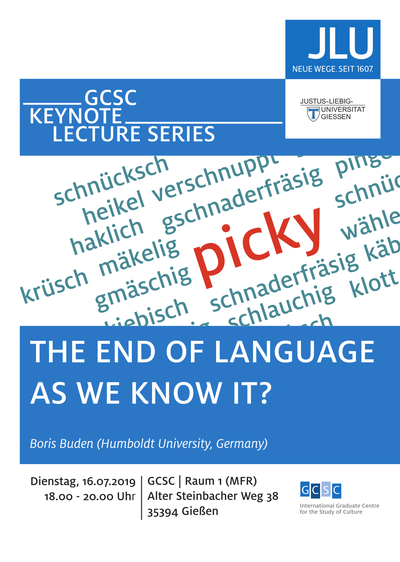

Boris Buden (Humboldt University Berlin, Germany)

The End of Language as We Know it?

16.07.2019, 18-20, room 001, MFR

Abstract

This is quite old news: the German spirit is dying again. This time, however, its passing away seems to be more dramatic than ever before. The deathbed on which it is lying today is in fact its own very cradle – the German language. The latter is rapidly deteriorating in the process of its re-vernacularization. This is at least what is claimed by Jürgen Trabant in his book Globalesisch oder Was/ Ein Plädoyer für Europas Sprachen. He understands this process as a new socio-linguistic and cultural condition that resembles the Europe of the Middle Ages, when Latin was used on all the higher levels of social, political or intellectual life, while the lower social strata were speaking the old vernaculars. Nowadays, however, it is English that has taken the role of the new lingua franca. It is spoken in all the higher and more important discourses of today’s Europe, forcing German and other European “cultural languages” to retreat onto the level of everyday life and less important discourses. At stake is a regression into a neomedieval diglossia. What are the social and political consequences of this development? How does it affect cultural relations within our societies and globally? Has it an impact on the existing forms of disciplinary knowledge production? The lecture will tackle these questions from the perspective of translation as a theoretical concept and a socio-cultural practice.