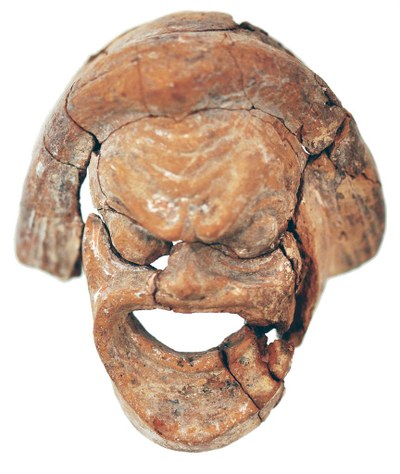

Comic theatre mask, Inv. T I-19 „leading slave“

|

|

Comic theatre mask, Inv. T I-19 „leading slave“ Front from the mould, back hollow, smoothed. Reddish brown (2.5YR 6/6) clay with many dark inclusions. White engobe. Remains of painting in red-orange in the folds, traces of pink under the right eye, above the right brow and on the upper lip. Light pink on the left cheek. Provenance: Unknown; acquired by Bruno Sauer from the Margaritis Collection in 1899. State of preservation: Composed of many fragments, restored in 2005 (E. Fuertes, Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste Stuttgart, workshop no. B 562/8). Dimensions: H: 6,1 cm; W: 7,1 cm; D: 9,0 cm. References: W. Zschietzschmann, Gießener Antiken, Hessische Heimat 15/ 18.7.1962, 57-60 fig. 4. |

Description: Above the high forehead is a roll of hair, the speira[1], which continues in longitudinally streaked hair bundles that increase in volume towards the bottom. The short, protruding beard forms a funnel around the wide-open mouth with its thin, plastic lips. While the upper lip runs horizontally, the lower lip curves downwards.

The eyeballs bulge out hemispherically between the plastically indicated lids. A deep vertical furrow is carved above the sunken root of the nose between the raised, steeply rising eyebrows. The forehead wrinkles take up the oscillation of the brows with progressive attenuation.

Commentary: The speira is a feature of the "leading slave", Hegemon Therapon[2]. This is a male role in Attic New Comedy[3], whose protagonists were widely distributed throughout the Hellenic world in the form of terracotta statuettes. The Giessen mask T I-19 can be assigned to the type of the "leading slave". Comparable is, among others, a specimen in London[4], allegedly from Melos, decorated with a vegetal wreath. As the studies of Webster and Bieber revealed[5], representatives with a deep round bell around the open mouth still date to the 3rd century BC[6]. Then the shape of the funnel changes and gradually approaches a semicircle around 200 BC; beard strands are also indicated[7]. Another temporal stylistic criterion is the pupil bore, which, appropriately positioned, can create the impression of squinting[8]. Examples of this are provided, among others, by the finds from Priene, which are dated to the middle or 2nd half of the 2nd century BC[9]. As a result, the funnel formation of the beard weakens, as does the curve of the forehead wrinkles. The corners of the mouth taper, the hair is streaked crosswise and springs up so far that it protrudes from the cheeks[10].

The speira of the Giessen mask, on the other hand, shows a vertical streak that is limited to the lowest section of the hair bundles. The mouth and beard form rounded triangles with the tip pointing downwards. The hemispherical eyeballs are not pierced. T I-19 is therefore likely to be almost at the beginning of a development that spread through the Greek Koiné in the Hellenistic period[11] and continued into the Roman Imperial period[12]. Based on the colour of the clay, the piece could have been made in Attica.

Determination: Late 3rd century BC, Attic?

[1] C. Robert, Die Masken der neueren attischen Komoedie, HallWPr 25, 1911, 3, after Pollux Δ 2.

[2] Robert ibid.

[3] M. Bieber, The History of the Greek and Roman Theater (Princeton 1961) 92, 102, fig. 324, 396; T. B. L. Webster, Leading Slaves in New Comedy 300 B. C. – 300 A. D., JdI 76, 1961, 100-110; Robert 1911, 3-7; Pollux IV, 149.

[4] L. Burn – R. Higgins, Greek Terracottas in the British Museum III (London 2001) 112 no. 2267 pl. 47; without headdress from Smyrna: P. Leyenaar-Plaisier, Les terrescuites grecques et romaines Leiden 1979, 482 no. 1378 pl. 177; from Athens: F. W. Hamdorf, Hauch des Prometheus (München 1996) 158 fig. 187; id. ibid. 164 Abb. 198.

[5] Bieber ibid. 40-48. 87-107; a statuette from Taranto depicting the leading slave as Kourotrophos with a child on his arm, id. ibid. 103 no. 400; Webster 1961, 100-110; id., Monuments Illustrating New Comedy (London 1969).

[6] L. Frey-Asche, Tonfiguren aus dem Altertum. Antike Terrakotten im Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe (Hamburg 1997) 87 f. fig. 58.

[7] Webster 1961, 102 f. fig. 3.

[8] L. Bernabò Brea, Menandro e il teatro greco nelle terracotte liparesi (Genova 1981) 205 fig. 339. 340; B. Vierneisel-Schlörb, Kerameikos 15. Die figürlichen Terrakotten 1 (München 1997) 97 no. 293 pl. 56.

[9] F. Rumscheid, Die figürlichen Terrakotten von Priene (Wiesbaden 2006) 528 f. no. 378-381 pl. 157 f.

[10] K. G. Kachler – S. Aebi – R. Brunner, Antike Theater und Masken (Zürich 2003) 28; C. Robert, Die Masken der neuen attischen Komödie, 25. HallWPr 1911, 77, fig. 94. 95; Rumscheid 2006, 529- 530, no. 381, pl. 158, 1-2; Bieber ibid. 104 no. 405; P. C. Bol – E. Kotera, Bildwerke aus Terrakotta. Liebieghaus Frankfurt am Main (Melsungen 1986) 134-136 fig. 69. p. 173 fig. 86.

[11] Hamdorf 1996, 163 fig. 194; S. Moraw – E. Nölle, Die Geburt des Theaters in der griechischen Antike (Mainz 2002) 132 fig. 165. 166.

[12] Bieber ibid. 156 fig. 566; ulostherápon, Bernabò Brea ibid. 137 fig. 225.