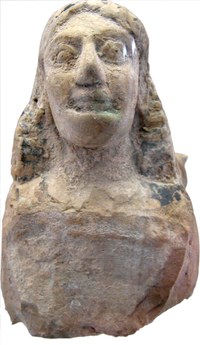

Female Protome, Inv. T I-6

|

Female Protome, Inv. T I-6. Front side of the head from the mould, back side not finalised, smoothed. Provenance: Unknown. State of preservation: Front section of the bust lost. Break at the back below the neck, with sharp-edged projection. Injuries to the ears and in the hair. Dimensions: H: 7,3 cm; W: 4,9 cm; D: 2,5 cm. References: Not published.

|

Description: The rectangular head tapers trapezoidally towards the bottom. The hair forms a pediment slightly shifted to the right above the forehead, which it frames in short arches. Below the temples it falls in broadening plastic steps onto the shoulders and merges into painted vertical strands[1].

Smooth, angular cheeks end in a massive chin, which is set off from the closed mouth by a horizontal indentation. The full lips are cut straight. A bulky nose protrudes between large pre-squinting eyes; it forms a straight line with the forehead. The eyes lie under high orbitals and are bordered by bulging lids. The lower lid is indicated almost horizontally, the upper lid highly curved. Within the eyeball the iris is indicated by a circular depression. A dark dot marks the pupil.

Commentary: The protome T I-6 probably belonged to a pyxis as a figural handle, and specifically to a round pyxis because of the convex wall[2]. As the sharp edge on the back of the Giessen specimen[3] and the completely preserved representatives of female-headed pyxides[4] show, such busts were applied to the shoulder of the vessel so that the back of the head supported the lip of the pyxis. On the back, the figures in the middle section are mostly freely formed, not elaborated, but occasionally painted. The vessel type was produced in Corinthian workshops at the end of the 7th/beginning of the 6th century BC and was part of the formal repertoire of Archaic pottery until the late Corinthian period[5]. Like the other pottery from Corinth, the head pyxides spread beyond the Greek heartland to Eastern Greece and the Apennine Peninsula, to Etruria, and Sicily[6].

Well-preserved head pyxides come from Selinunte, others are kept e.g. in New York, San Simeon/CA, Okayama[7]. Head T I-6 resembles a specimen in Copenhagen and pyxis heads in New York as well as in the Louvre[8]. Like those, it reflects the shoulder hair of the hairstyles of the Daedalian period, which is divided into flat steps. Stylistic details such as the additive relationship of the front and side views to each other, the bulky chin and the spherically bulging eyeballs between the flat lower eyelid and the high arch of the upper eyelid are reminiscent of the time of large-scale statues such as those of the Kuros New York[9]. In the case of the terracotta heads obtained from moulds, however, it should be borne in mind that they could already be present in the Middle Corinthian, i.e. in the 1st quarter of the 6th century BC, but were only used as pyxis heads at a later date, which can be dated to the Late Corinthian, for example, by the painting of the vessels and the letter form of the inscriptions[10].

Determination: Mid 6th century BC, from Corinth.

[1] In contrast, plastically indicated vertical strands of hair: K. Wallenstein, Korinthische Plastik des 7. und 6. Jahrhunderts vor Christus (Bonn 1971) 67-68 pl. 12, 1.

[2] Female head pyxids are provided with two or three handles: Chr. Dehl-von Kaenel, Die archaische Keramik aus dem Malophoros-Heiligtum in Selinunt (Berlin 1995) 169 f. 188-191 pl. 32 ff.

[3] Wallenstein ibid. 114 pl. 8, 5.

[4] St. Böhm, Korinthische Figurenvasen. Düfte, Gaben und Symbole (Regensburg 2014) 22 f. 121-123. 130 f. 133. 136. 145; Dehl-von Kaenel ibid. 188-191 pl. 32 f.; "Protome pyxis", E. Simon, The Kurashiki Ninagawa Museum Okayama (Mainz 1982) 34-36 fig. 15; "Female Protome, pyxis handle", F. Johansen, Greece in the Archaic Period (Copenhagen 1994) 155 f.; „Head-Pyxis“, D. A. Amyx, Corinthian Vase-Painting of the Archaic Period (Berkeley – Los Angeles – London 1988) 224 pl. 93. 451-453; "Pyxides with Handles in the Form of Female Heads or Busts", H. Payne, Necrocorinthia (Oxford 1931) 306 f. pl. 47 f.; V. Karageorghis, Ancient Art from Cyprus.The Cesnola Collection in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York 2000) 102 fig. 162.

[5] Amyx ibid. 452.

[6] Dehl-von Kaenel ibid. 188-191 no. 1203. 1204 1206 pl. 32 f. On the foundation dates of Greek colonies and their significance for the chronology of Corinthian pottery: B. Bäbler, Archäologie und Chronologie (Darmstadt 2004) 72-82; J. Boardman, Kolonien und Handel der Griechen (München 1982) 195-247.

[7] Dehl- von Kaenel ibid. 188 f. no. 1203 pl. 33; Karageorghis ibid. 102 fig. 162; Amyx ibid. 224 pl. 93 1 B; Simon ibid. 34 f. fig. 15.

[8] Johansen ibid. 156 fig. 117; Karageorghis ibid. 102 fig. 162; F. Croissant, Tradition et innovation dans les ateliers corinthiens archaïques: Matériaux pour l'histoire d'un style, BCH 112, 1988, 112 f. fig. 39. 42.

[9] W. Martini, Die archaische Plastik der Griechen (Darmstadt 1990) 4 f. fig. 1. and p. 175.

[10] Böhm ibid. 131 note. 339; Dehl-von Känel ibid. 189 note. 416; F. Lorber, Inschriften auf korinthischen Vasen (Berlin 1979) 92 f. no. 153 fig. 60; Karageorghis ibid. 102 fig. 162.